Exhibitions

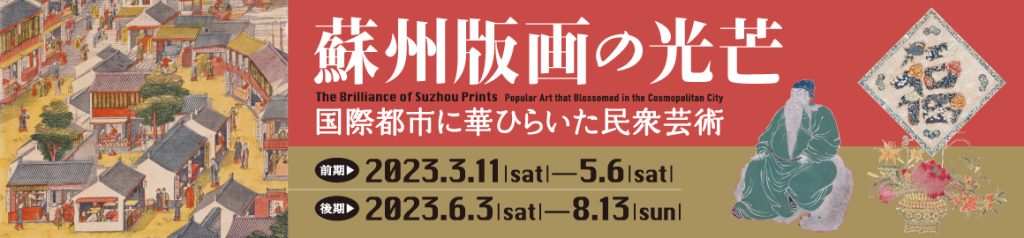

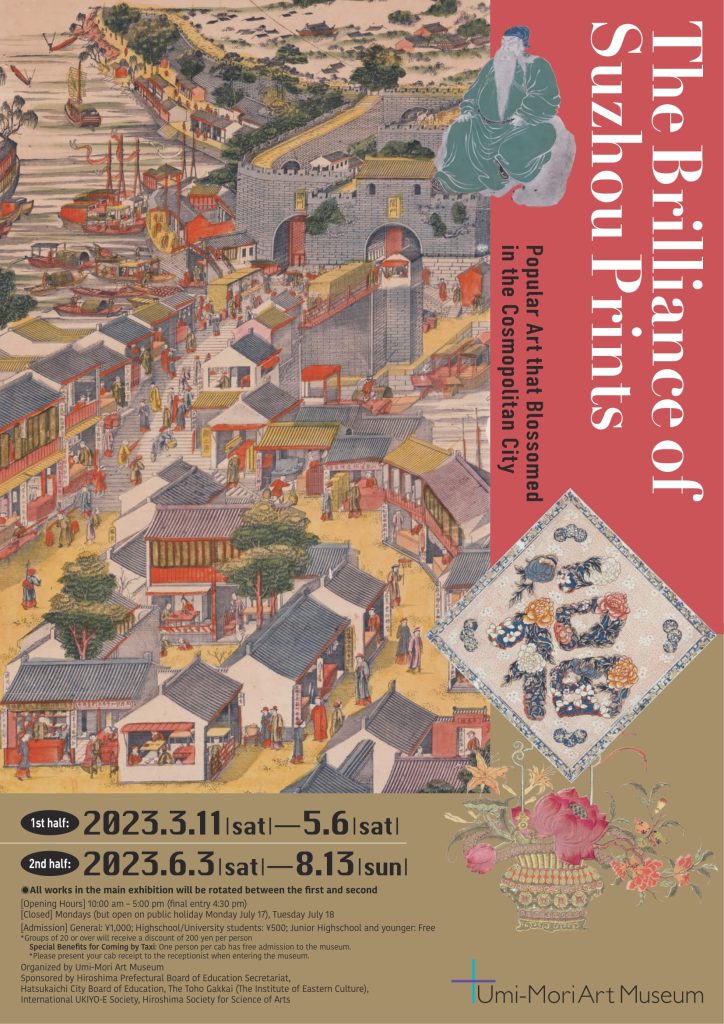

The Brilliance of Suzhou Prints – Popular Art that Blossomed in the Cosmopolitan City

Historically, prints with auspicious themes, landscapes, flowers and birds, and beautiful figures have enriched the lives of people in China.

Most astonishing in that long history was the birth of a revolutionary popular art form now commonly called “Shuzhou prints”, which occurred in the cosmopolitan city of Shuzhou in the 17th and 18th centuries, combining Chinese and Western art traditions. It was a powerful force that did not stop with Chinese art, but went on to influence art abroad, such as in Japan and Europe.

Unfortunately, many of these Shuzhou prints were discarded in the course of everyday life, and very few have been passed down to present times, meaning we have not developed a deep understanding of the full picture.

In terms of both quality and quantity, the Umi-Mori Art Museum holds the world’s foremost collection of Chinese prints, with over 3,000 works including rare Shuzhou prints from the 17th and 18th centuries, as well as works from contemporary times. In this exhibition we have selected approximately 300 works from the museum collection, including works publicly exhibited for the first time, in the hope that visitors will enjoy this previously unknown world of Chinese prints.

自古以来,中国人的生活中就被年画、风景画、花鸟画、仕女画等各种版画点缀着。

在悠久的历史中,令人瞩目的是在17和18世纪,苏州成为一个国际大都市时,中国和西方艺术的融合衍生了划时代流行艺术的形成,被当今称为苏州版画。这些版画的影响力之强大,不仅影响了以后的中国艺术,也影响了诸如日本、欧洲等其他国家的艺术。

遗憾的是,由于许多苏州版画注定要在日常生活中被消耗和丢弃,因此存留下来的遗物很少,它们的全貌也无从知晓。

海杜美术馆所收藏的中国版画,其完好的保存质量及数量均属世界首屈一指。从罕见的17-18世纪的苏州版画到现代年画,共计3,000多件作品。本次展会选取了博物馆藏品中的300件,多数均为首次展出的珍品,尽情享受这未知的中国版画世界吧。

English ver.

Chinese ver.

Download the exhibition list from here

General Information

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday (except July 17th), and July 18th

Admission: General admission: 1,000 yen, High school/university students: 500 yen, Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education, The Toho Gakkai (The Institute of Eastern Culture), International UKIYO-E Society, Hiroshima Society for Science of Arts

基本信息

开放时间:10:00~17:00(最后入馆16:30前)

休馆日:每周一(但7/17[周一]为节日开放, 故7/18[周二]休馆)

入馆费:成人票1,000日元 / 高中及大学生500日元 / 中学生以下(中学生含)免费

*20人以上的团体,每人减免200日元

[出租车来场人员的优惠]对于乘坐出租车来展馆的

主办方:海杜美术馆

支援方:广岛县教育委员会, 廿日市市教育委员会, 东方学会, 国际浮世绘学会, 广岛艺术学会

Event Information

Commemorative conference: “The Current State of Research on Chinese Prints”

Simultaneous interpretation in Japanese, Chinese, and English Online Zoom meeting (URL will vary according to language)

Saturday May 27, 17:30–21:00

Speakers: KOBAYASHI Hiromitsu (Honorary Professor, Sophia University), ITAKURA Masaaki (Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, University of Tokyo), ŌKI Yasushi (Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, University of Tokyo), TAJIMA Natsuko (Ome Municipal Museum of Art), AOKI Takayuki (Umi-Mori Art Museum)

Sunday May 28, 17:30–21:00

Speakers: Yu-chih Lai (Academia Sinica), Anita Xiaoming Wang (Birmingham City University), Anne Farrer (Sotheby’s Institute of Art), Lucie Olivova (Masaryk University), CvdB (pending)

Supported by The Japan Art History Society

How to participate: Send an email with your name and affiliated

institution to: prints@umam.jp. Before the conference, a link will be sent to applicants, including a User ID and password.

Application deadline: Saturday May 20, 2023

Umi-Mori Art Museum Curator Gallery Talk

Schedule: Sat. March 25, Sat. April 29, Sat. June 24, Sat. July 29, Sat. August 12; each at 1:30 pm

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum Exhibition Hall

Participation fee: Free (museum entrance fee required)

Pre-registration: Unnecessary

Summer Vacation Workshop

*To be announced on the museum website in early July, 2023

展会信息

纪念演讲会“中国版画的当前”

语言:日中英3国语 同声传译

地点:zoom线上演讲会(根据语言, 使用不同URL)

5月27日(周六), 17:30–21:00

演讲者:小林宏光(上智大学名誉教授), 板仓圣哲(东京大学东洋文化研究所), 大木康(东京大学东洋文化研究所), 田岛奈都子(青梅市立美术馆), 青木隆幸(海杜美术馆)

5月28日(周日), 17:30–21:00

演讲者:Yu-chih Lai(中央研究院), Anita Xiaoming Wang(Birmingham City University), Anne Farrer(Sotheby’s Institute of Art), Lucie Olivova(Masaryk University)

支援方:美术史学会

参加方式:填写姓名及所属单位并发送邮件至 prints@umam.jp.

演讲会的前日会将URL, ID以及密码发送到您本人报名时用的邮箱

截止时间:2023年5月20日(周六)

本博物馆的画廊讲座

时间:3月25日(周六), 4月29日(周六), 6月24日(周六), 7月29日(周六), 8月12日(周六)。每周六 13:30~

地点:海杜美术馆展示厅

费用:免费(入馆费用需要)

事先报名:不需要

夏令研讨会

自2023年7月上旬起于网站介绍.

Section 1: Depicting Legends, Historical Events, and Literary Tales

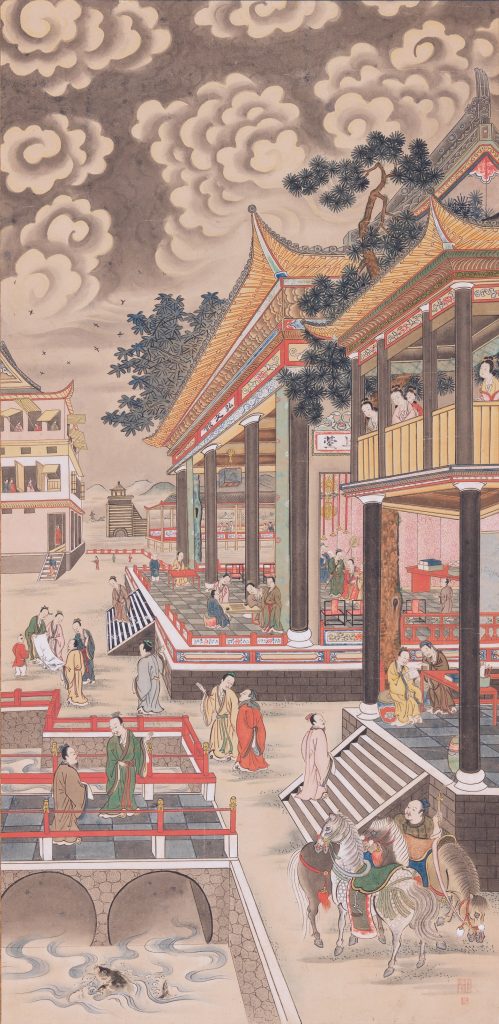

In the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912), when there was no television or internet, the most common way for people to come in contact with literary tales was word of mouth, theatrical performance, or printed matter. Of those, it was printed matter that people could keep on hand and enjoy on their own.

Books of the time were costly items, aimed at the limited number of people who could read. In contrast, prints were sold one sheet at a time and therefore inexpensive, and even if one could not read the text, the content of the story could be appreciated through the pictures alone, making it easy for common people to enjoy. Of course, prints depicted stories famous enough to become books in their own right, but also illustrated stories that people might encounter firsthand in the course of everyday life, such as narratives sung on the streets accompanied by the sanxian or pipa lute, or classical Chinese opera performances accompanied by the erhu, yueqin, tongluo, and other musical instruments.

Chinese prints were an art for the masses, that people could easily enjoy at home. Therein quietly lie the numerous stories of human emotion and drama that people of all ages and social classes enjoyed at the time.

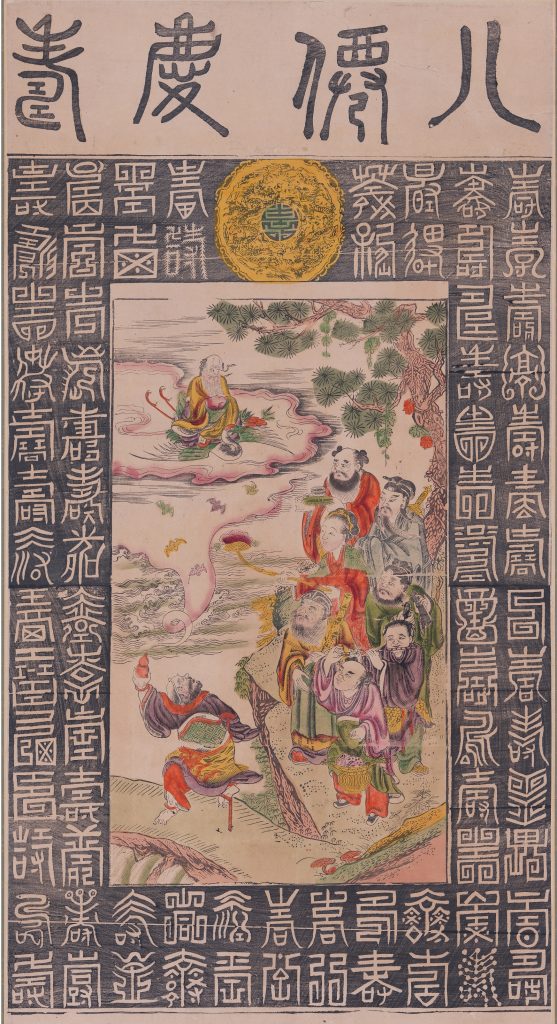

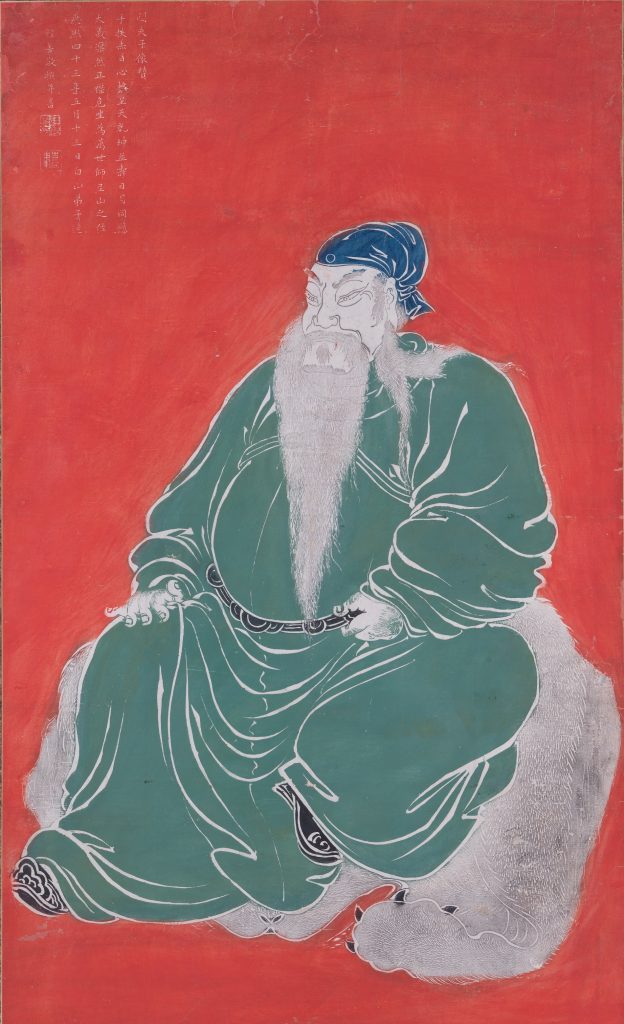

Section 2: Depicting Deities and Saints

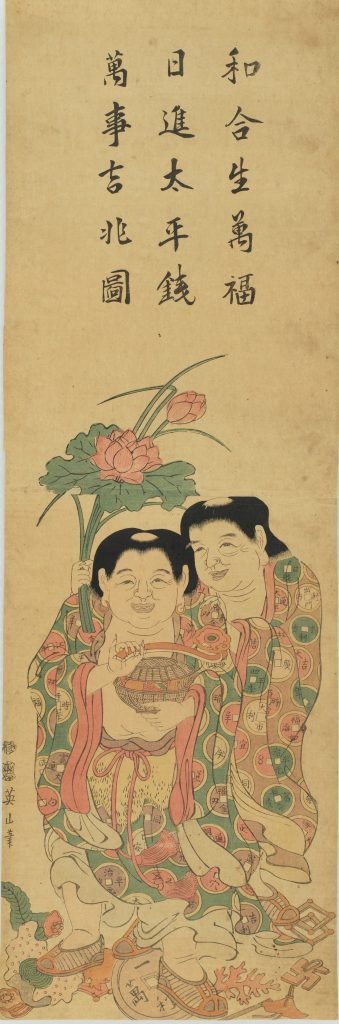

Religious deities are one of the main themes found in Chinese prints.

A great number of prints depicting Taoist deities and those of popular folk religion were made for the common people, who wished for happiness throughout the year, safe childbirth, long life, prosperous business, and so on. Typical examples include the Gods of Happiness, Fortune, and Long Life; the Eight Immortals; the God of Longevity; Ma Gu; and Guan Yu. The breadth of expression characteristic of Chinese prints, as seen in the variety of ways in which the Gods of Happiness, Fortune, and Long Life were depicted, speaks to the broad-minded nature of the religious beliefs held by the common people. The historical figure Guan Yu became “Emperor Guan”, and was deified in Chinese folk religion, depicted in prints as the center of a triad, flanked by Zhou Cang and Guan Ping. A sort of cult developed around Guan Yu, and we can identify a number of Chinese prints in which he was depicted as a god.

Please enjoy these works, which were once a familiar presence that combined faith and art, rooted in the everyday lives of the common people.

Section 3: Depicting Figures

There are many wonderful Chinese prints that depict figures. The majority of such works from the early Qing Dynasty depict the refined lifestyles of noble women in the imperial court. By the late Qing Dynasty, they came to feature common people going about their everyday lives.

More works feature women and children than men, often accompanied by things like flowers and birds, or mythical creatures such as the qilin. This is because in the visual arts of the time, importance was attached to auspicious symbols that expressed wishes for an abundance of children, success in life, riches and honors, and longevity.

In addition to the graceful expression of movement, clothing, and shading in these images, we can observe that faces were also rendered in fine detail. In many works, the printed faces were painted over in white, after which the eyebrows, eyes, noses, and mouths were carefully traced over with a fine brush, rouge added to the lips, and shading applied to highlight and enhance other features. Please enjoy these prints of figures, whose expressions have been enlivened with the touch of a brush.

Section 4: Depicting Flowers and Birds

Before full-fledged multi-color ukiyo-e printing was achieved in Japan, in China multi-color prints were being embossed to produce beautiful, single-sheet flower-and-bird images. Worthy of special mention are a group of prints made by Ding Liangxian (dates unknown) and Ding Yingzong (dates unknown) (one theory suggests they were in fact the same person) from the Yongzheng period (1723–1735) to the early Qianlong period (1736–1795). Without using the key block in the flower section, they created vivid, three-dimensional images using the color blocks and embossing techniques alone.

Fundamentally, the motifs depicted in these flower-and-bird images contain auspicious meanings. For example, works that combine the lotus flower, pomegranate, and orange daylily mean that without fail, one will be blessed with children (lotus), give birth to many children (pomegranate), and give birth to sons (orange daylily). While bird-and-flower images of splendid visual beauty, we can understand how people of the time viewed them by analyzing and interpreting their hidden meanings.

Section 5: Depicting Auspicious Symbols and Characters

Characters of the written language and graphic designs are also themes found in Chinese prints. Characters such as “Good Fortune” and designs with auspicious meanings were illustrated, including works that feature characters incorporating colorfully decorative motifs with deep, yet easily understandable meanings; and those with complicated devices that require an informed imagination in order to unravel how their characters should be read and interpreted. It is a group of works in which a single image can contain a layered network of meaning to be deciphered, with a fascinating depth like that found in fine poetry.

In addition to the literal meanings of the characters and the beauty of their shapes, in some works the lines of the characters are rendered with auspicious plants and flowers, in others narrative images that convey the meaning of the character are featured within its shape, while in still others characters are set against backgrounds completely covered in auspicious patterns. They overflow with a variety of designs that viewers could never tire of.

Section 6: Depicting Landscapes and Customs

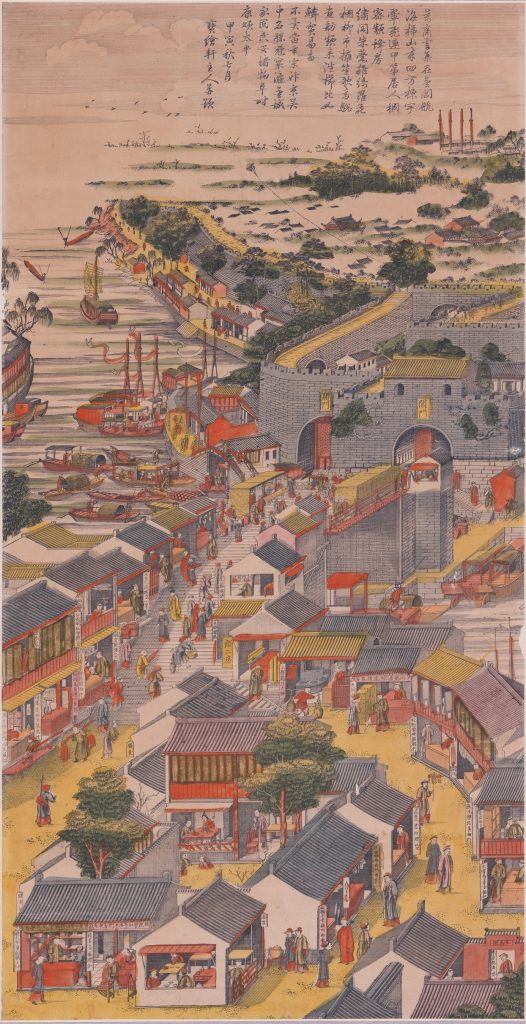

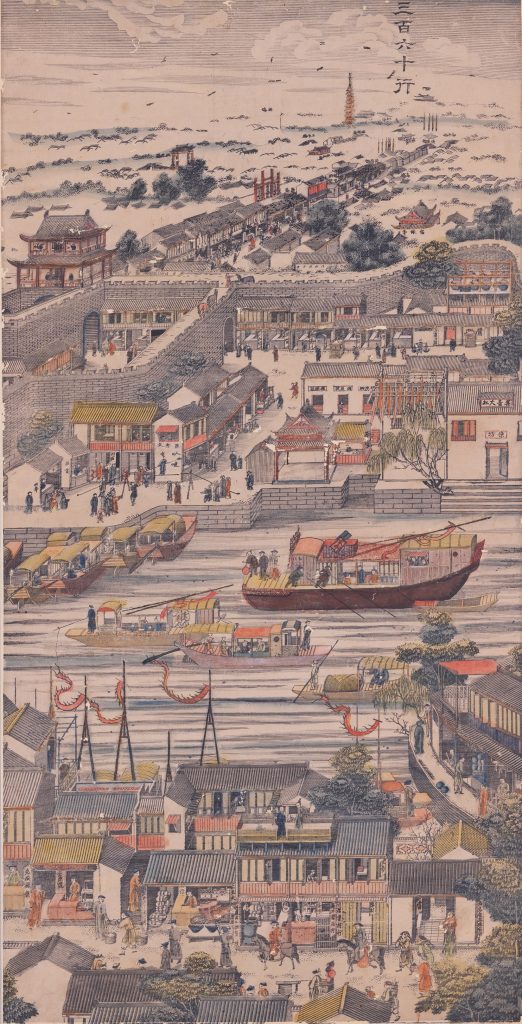

From the late Kangxi period (1662–1722), Suzhou and surrounding areas began making prints that imitated Western images. These are prints that use linear perspective, shading, and hatching techniques seen in copperplate prints. Among them are works that have things such as “brushwork imitating the Great West” (imitating Western methods of depiction) written within the image itself, clearly establishing the connection. In the beginning, they employed Western techniques with precision, but over time Western elements began to disappear, and by the mid-Qianlong period (1736–1795) a unique, hybridized Chinese-Western style emerged.

In depictions of urban landscapes, the landmarks, appearance of festivities, trends, and fashions of the time were all rendered in great detail. Also in this section, we have gathered prints that were direct parts of people’s everyday lives, such as war reports, maps, and boardgames. While of great artistic merit, these are also important documents that allow us to understand the circumstances of a time from which there are no photographic records.

Section 7: The Transmission of Chinese Prints to Japan

A Chinese type of printed paper called rōsen (paper with embossed patterns) was used in a fragment of the ninth volume of the Kokin wakashū (12th century, Important Cultural Property) attributed to Minamoto no Toshiyori (1055–1129). In addition, copies of the woodblock-printed Mahā-prajñā-pāramitā sutra (12th century) made at the Qisha Yansheng temple in Pingjiang county were produced at Kōfukuji and other temples in Nara in the late 12th century. In this way, printed Chinese material has come to Japan and played a part in Japanese culture since ancient times. Chinese prints also went to Europe, and recent research has revealed the influence they have had in a number of different places.

In this section, we exhibit prints from the Umi-Mori Art Museum collection that have come to Japan since the 17th century, and trace the influence they have exerted. Including ukiyo-e created with ideas taken from them, this is a group of works in which you can feel the direct impact of the transmission of Chinese prints to Japan.

Section 8: Almanacs, Door Guardians, and Religious Zhima Prints

Almanacs

There is a detailed almanac illustrated in the upper left corner of work number 137, “Flowers in Vase”, which is a Chongzhen calendar in booklet form, but the more commonly used type of almanac was a single printed sheet of paper, an example of which is illustrated in the lower right corner of the same work. They include the long and short months of the lunisolar calendar, the 24 distinct solar periods within that calendar, as well as cycles of fortune and misfortune.

Many of these simplified almanacs feature auspicious illustrations, or images of the so-called “tutelary deities of the hearth”. These deities serve the role of ascending to heaven once a year to report on families, on the 23rd day of the 12th month of the Chinese calendar. On that day, families gather for a great cleaning of the hearth, they replace the old image of the deity with a new one, and offer sweets so that it will be reported to the god Shangdi that they are living in harmony. As images of these deities were kept in place for a full year, it was convenient to add almanacs to them.

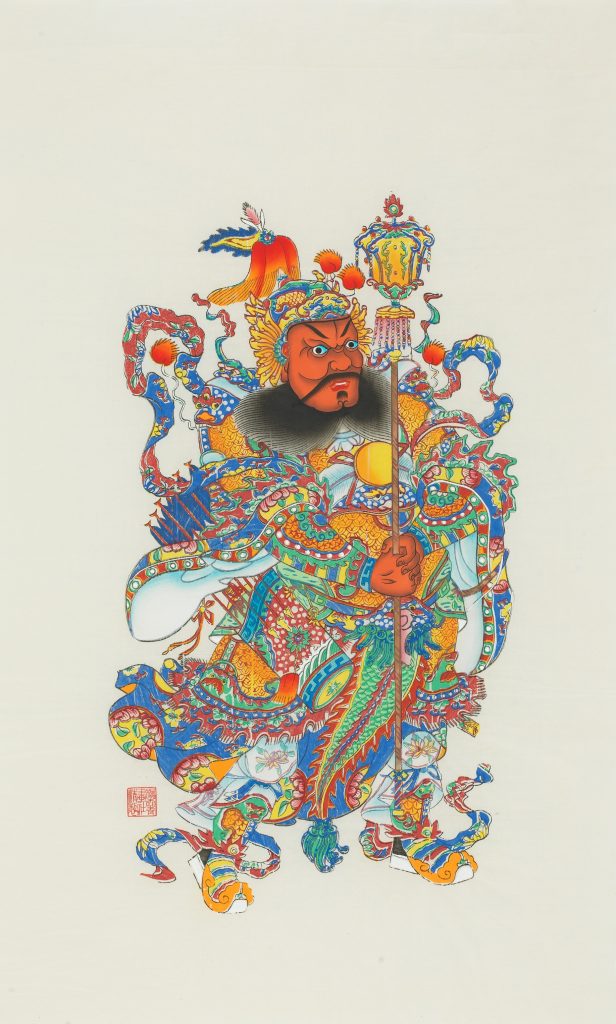

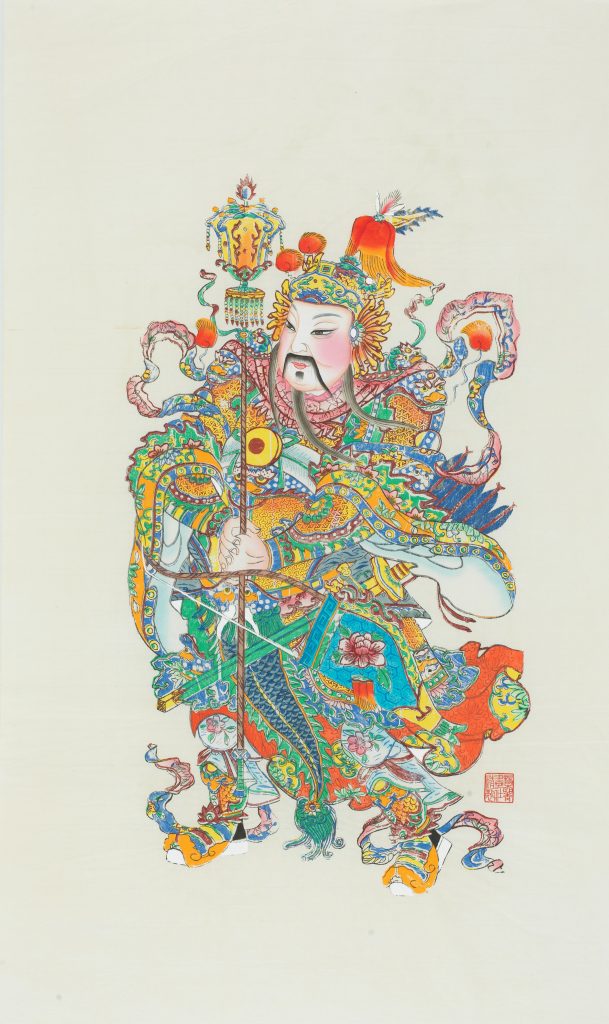

Gate Guardians

Gate guardians are protective deities that block the entrances of homes to safeguard families against disaster and disease. There are cases of large households with these guardians painted directly on their entryways, but in common homes woodblock printed images were affixed to the outside of entrance doors once a year on the Lunar New Year with the hope for peace and tranquility throughout the year.

In the case of double doors that open in the center, individual guardians were affixed to the right and left doors to form a pair. There are many paired images of Qin Shubao (Qin Qiong) and Yuchi Jingde (Yuchi Gong) for such double doors, and in the case of single doors, images of Zhong Kui were common.

Here we exhibit gate guardians from all parts of China that were produced in the 1940s. In certain places where print making thrived at the time, such as Yangliuqing, specialized craftsmen made these prints, but in general they were not created by specialists, but rather by common people engaged in agriculture. They made them in the slow season, after the autumn harvest was complete.

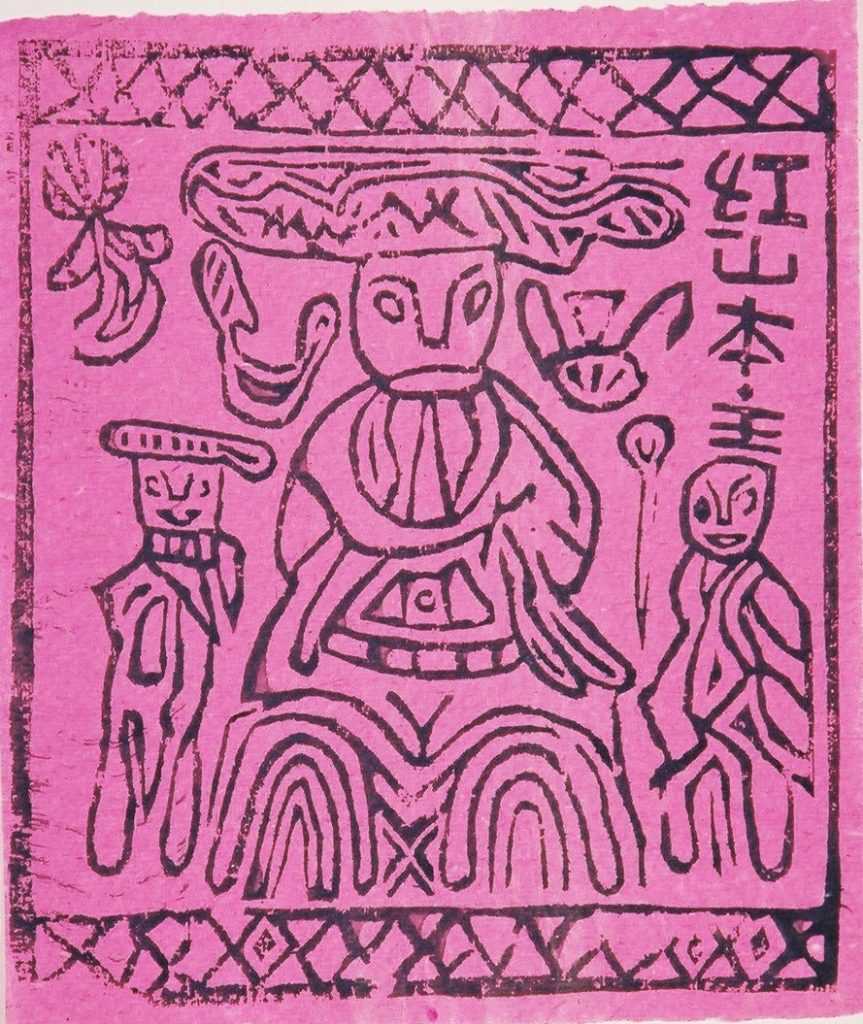

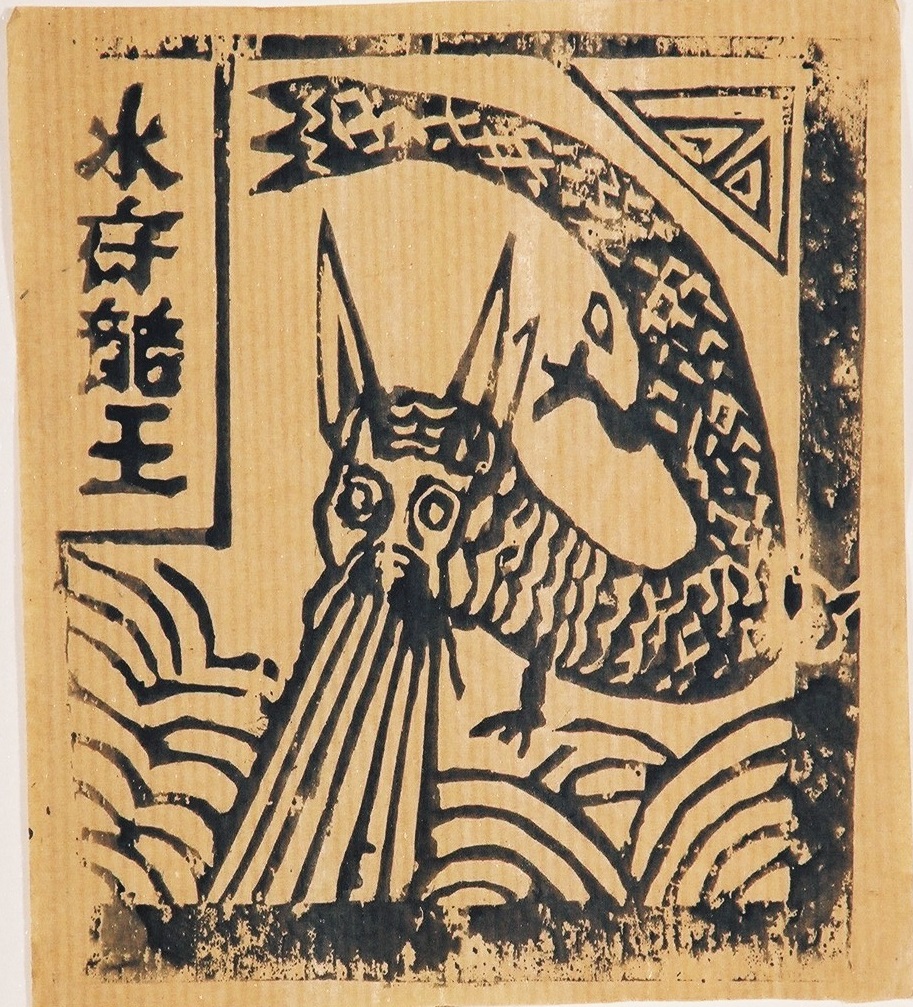

Religious Zhima Prints

Religious zhima prints, literally “paper horses”, are images of deities printed on paper of various colors. They were largely offered in Taoist ritual ceremonies, and when the service finished, they were burned in worship.

Here we display examples of these religious prints made in Dali, Yunnan Province. In Yunnan Province, as a result of the Han migration after the Ming Dynasty, these prints became popular among ethnic minority groups. Eventually their use was limited not only to ritual ceremonies, but became indispensable parts of many aspects of everyday life, such as marriage, child birth, and the construction of new buildings. It is said that Yunnan did not lose the custom of producing these essential items for the common people, even in the 1960s and 1970s when ceremonies using zhima were deemed superstitious and done away with throughout the country.

The zhima of Yunnan are called jiama or jiamazi. Both of these terms literally mean “armor clad horses”, but in modern times the variety of deities depicted is limited only by the imagination. And it is not leaders of the religious community whose imaginations create these deities, but the common people themselves.

Almanac Celebrating Thirty-seven Years of the Qing Dynasty Qianlong Emperor, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong 36(1771), Private collection

Door Guardian,People’s Republic of China, 1980s, Yangliuqing, Tianjin City, Private collection

Religious Jiama Print, People’s Republic of China, 1980s, Dali, Yunnan, Private collection