Exhibitions

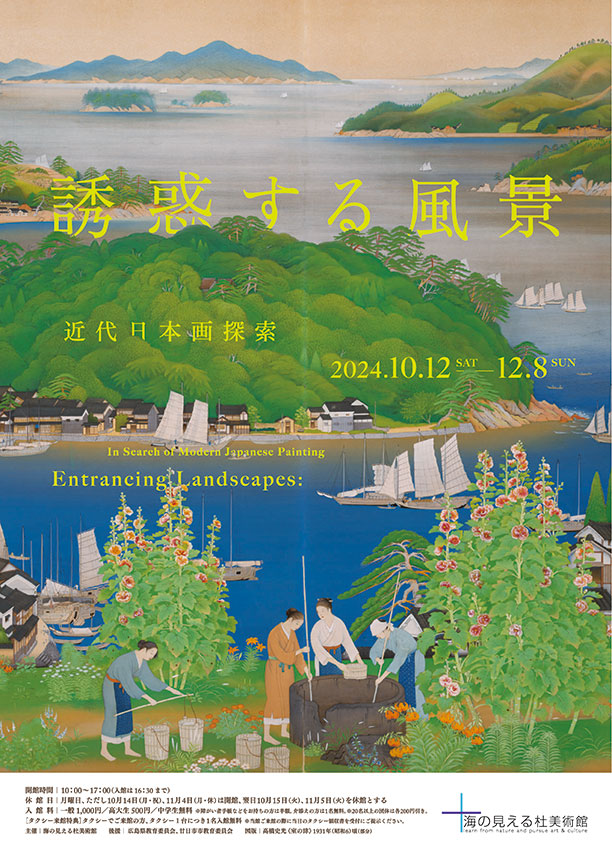

Entrancing Landscapes: In Search of Modern Japanese Painting

Introduction

Welcome to Entrancing Landscapes: In Search of Modern Japanese Painting, an exhibition that explore Umi-Mori Art Museum’s collection of modern Japanese paintings themed around “landscapes.”

In the past, Japanese paintings often took the form of “sansuiga” (“mountain and water paintings”), an artistic tradition inherited from China. These sansuiga works portrayed idealistic worlds that resided within the souls of the artist or their audiences, worlds filled with mountains, valleys, rivers, dwellings and the hermits who lived there. In early modern times, paintings also began depicting famous places and views as they actually appeared. As Western ideas and art arrived during the Meiji era, the concept of “landscape paintings” also became entrenched in Japan too. “Landscapes” emerged as a major new genre of modern Japanese art, with many artists painting the scenery at various locations throughout Japan.

Nowadays we are surrounded by landscapes and rich scenery and we are captivated by the sheer beauty of nature. We also feel the same way about the paintings that capture these landscapes. This exhibition introduces paintings of these landscapes that soothe our souls with their natural beauty. In doing so, it explores how these landscapes were formed in the modern era and how artists selected them, imbued them with value, and set about portraying them in paint. Each society gradually forms its own ideas about which scenery it considers beautiful and valuable. The issue of how to approach and paint these landscapes is influenced by the desires of each artists, but it is also shaped by this social background and by the type of things people want to view and appreciate. Many of the aspirations of modern Japan are hidden in plain sight in modern landscape paintings. In these, we can glimpse the intentional actions of the government to protect nature, for instance. They also reflect the ongoing development of cities and modern civilization like railways, for example, as well as a newly-discovered nostalgia for the suburbs and countryside that emerges from this urban development. A further trend is the artistic search for a utopia in Japan’s southern climes. Landscapes may simply appear just as they are, but they actually contain something that lures us in and captivates us.

This exhibition explores modern landscapes through five chapters: Chapter One is entitled Shifting Scenery: “Sansuiga” and Landscapes, Chapter Two They Came, They Saw, They Painted: Depictions of Famous Places and Historic Sites, Chapter Three Discovered Landscapes, Chapter Four The Lures of Urban and Country Life, and Chapter Five The Utopias of the Artists. These modern landscapes fascinated the artists who saw them and they continue to enchant us to this day. We hope you enjoy your visit to this entrancing world.

General Information

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday (except October 14th and November 4th), and October 15th, November 5th

Admission: General admission: 1,000 yen, High school/university students: 500 yen, Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education

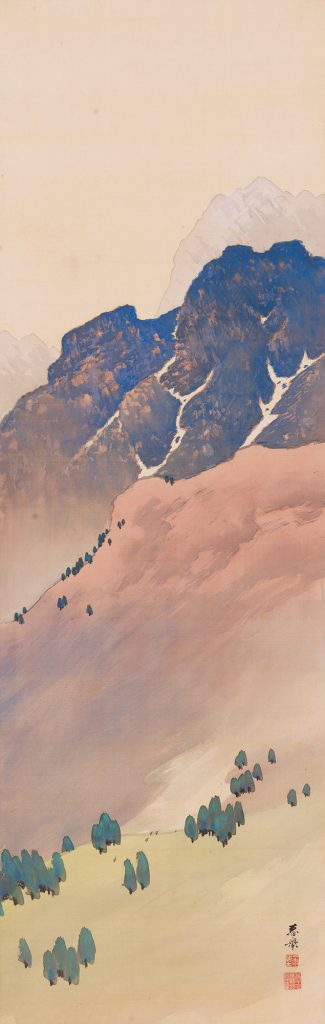

Chapter One. Shifting Scenery: “Sansuiga” and Landscapes

In the past, Japanese paintings of mountains, valleys and rivers mainly took the form of “sansuiga” (“mountain and water paintings”), an artistic tradition inherited from China. Rather than just portraying nature as seen with the naked eye, this tradition prioritized depictions of idealistic terrains or worlds that arose within the soul of the artist. From the mid-Edo period, though, painters experimented with more realistic depictions of nature. As Western ideas and art arrived from the Meiji era onwards, Japan also witnessed the creation of works we would now class as “landscapes.” Artists now strove to faithfully depict the outer world just as it appeared. During the Taisho era, meanwhile, some painters tried to imbue modern landscapes with a sense of emotion, sentiment and subjectivity using techniques from the older sansuiga tradition. This paradigm shift from “sansuiga” to “landscapes” is one of the major themes of modern Japanese art, though attempts to express the world still differed markedly between artist and period, even in the modern age.

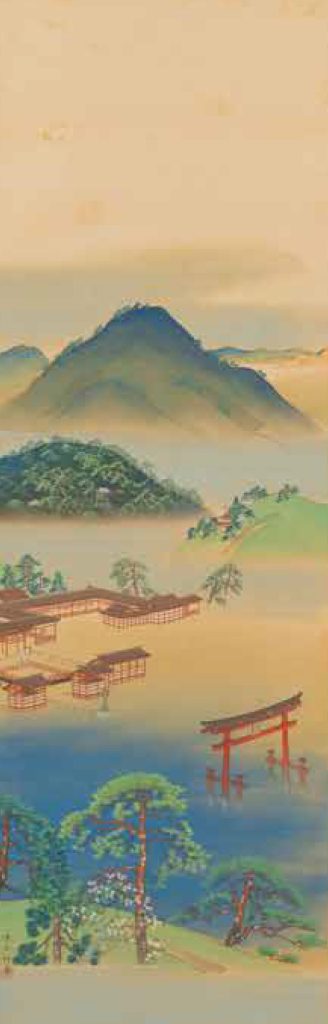

Chapter Two. They Came, They Saw, They Painted: Depictions of Famous Places and Historic Sites

From the Meiji era onwards, it became easier for regular folk to travel thanks to the removal of checkpoints and the evolution of transportation. Modern painters also began to visit and paint places where their artistic predecessors had once journeyed.

Yamato-e is a traditional painting style that depicts Japan’s unique nature and customs. From the Meiji era onwards, painters such as Matsuoka Eikyu (1881–1938) moved to revive Yamato-e traditions and imbue them with modern sensibilities and individuality to create new forms of expression. For these artists, famous places and historic sites were ideal subjects for their endeavors. Each artist approached these destinations with a different attitude. Some wanted to see these locations for themselves and put their impressions into paint. Others tried to uncover new picturesque qualities in places that had rarely roused emotions or inspired works in the past. We hope you enjoy these paintings of the famous places and historic sites visited by these modern artists.

Chapter Three. Discovered Landscapes

Nowadays, we can all enjoy visiting famous beauty spots in Japan to catch the views, make paintings and take photos. We tend to think we are viewing these landscapes as they have appeared since time immemorial. However, the beauty in these beloved sites is often a modified beauty that emerged when someone discovered this value in the past, added some new value to it, and maintained the site in its altered form. In the modern era, this often involves collaborations between government and industry, such as the establishment of national parks, the maintenance of Kyoto’s scenic beauty, and tourism. Painters have also played a role in this social movement by enhancing the value of these places through the act of painting them and creating beautiful artworks.

This chapter introduces these landscapes where artists “discovered” new values in the modern era.

Chapter Four. The Lures of Urban and Country Life

Tokyo, Osaka and other cities in Japan developed rapidly from the Meiji era onwards. Modern buildings proliferated alongside railways and other public facilities. Diverse forms of commerce and entertainment also flourished, with the streets bustling with ever more people. These transformations piqued the interest of the public and this led to the mass production of woodblock prints and other artworks depicting these townscapes.

The railways eventually wound their way to the city outskirts too, with several magazines popping up to extol the virtues of suburban life. As more people became more interested in the suburbs, painters also began depicting life in the outskirts of town, including Nakai Ginko (1901–1977), whose works feature here. In a way, this artistic movement to discover and capture the rustic simplicity of countryside life was itself a reflection of Japan’s ongoing urbanization.

Chapter Five. The Utopias of the Artists

From the end of the Meiji era, painters began to visit Japan’s warmer southern climes to paint. These included places like Toba on Mie Prefecture’s Shima Peninsula, Nakiri Village on Mie’s southeast tip, and the islands of Izu Oshima and Hachijojima. Here, they would paint the scenery, people working in local costume, and, in particular, the women of these regions. Komatsu Hitoshi lived in Ohara in northeast Kyoto and he would paint Ohara’s ladies and the surrounding countryside. Though close to Kyoto, Ohara was still very rural back then, with people mainly living by the fruits of their own labor. With their depictions of the tranquil, healthy life of the countryside, these paintings of Ohara and Japan’s southern regions captured a natural beauty untainted by civilization, a beauty gradually disappearing from the urban lives of these artists. Perhaps these painters found their own version of utopia in these idyllic locations.