Exhibitions

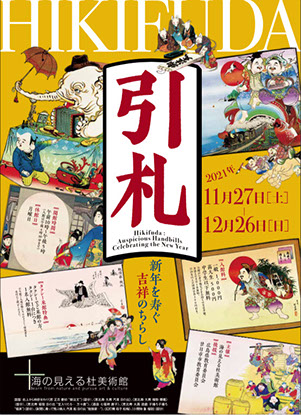

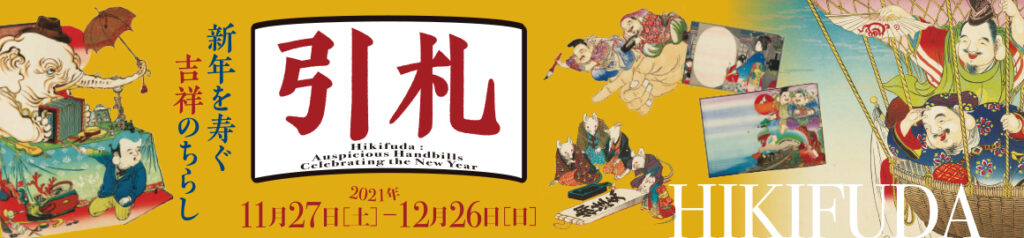

Hikifuda: Auspicious Handbills Celebrating the New Year

【Greetings】

Hikifuda handbills were produced from the Edo period (1603–1868) to the start of the Showa era (1926–1989). They were used by stores to advertise business, for example. They were hand printed using woodblock prints during the Edo period, though new forms of expression emerged during the Meiji era (1868–1912) as printers began to use copper plates, lithographic prints, typographic printing and other techniques imported from the West. Mass production then became possible following the epochal emergence of machine printing, with over 10 million handbills distributed each year during the late Meiji era, a figure surpassing the number of households in Japan at the time. Handbill designs grew more diverse as ukiyo-e practitioners, Japanese and Western-style painters and other artists entered the industry.

With a focus on handbills distributed at New Year during the Meiji period, this exhibition showcases around 150 items from Umi-Mori Art Museum’s collection of approximately 2,200 handbills. These are introduced by themes such as production date, printing techniques, artists, designs and characters. Made to celebrate the New Year, these handbills feature a variety of auspicious themes, from traditional motifs such as cranes and turtles, for instance, to designs reflecting the Meiji-era modernization process, such as the deities Ebisu and Daikoku bestowing riches from an airplane. The exhibition also features embossed handbills with feathers, petals and other motifs rendered in three dimensions. We hope you enjoy this glimpse into the blossoming ‘hikifuda culture’ that emerged through competition between artists, new printing technologies, and the colorful flamboyance of Meiji-era printed materials.

Finally, we would like to offer our deepest thanks to everyone whose support made this exhibition possible.

The organizers

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education

Dates: Saturday, November 27, 2021 to Sunday, December 26, 2021

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday

Admission:

General admission: 1,000 yen

High school/university students: 500 yen

Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Chapter One: Hikifuda Production Until Meiji 16 (1883)

Hikifuda handbills were first produced during the mid-Edo period. In the Meiji era, they were usually made the same way as ukiyo-e woodblock prints, with separate woodblocks used for each color. At the year’s end, stores would purchase handbills adorned with treasure ships and other auspicious motifs. These would be imprinted with the store name and handed out to regular customers. Handbills with calendars were popular, but the printing of calendars required authorization from the Meiji government, so handbill production was often handled by calendar wholesalers at the time.

Chapter Two: The Liberalization of Calendar Production and a Revolution in Printing

Many printing firms entered the handbill business after calendar production was liberalized in Meiji 16 (1883). This led to the use of copper plates, lithographic prints and other technologies not available when production was monopolized by calendar wholesalers. Several new techniques emerged from this competitive environment. These were sometimes combined with traditional techniques to engender new forms of expression. From Meiji 35 (1892), handbills were mainly produced by carving a design on a woodblock and transferring the design to a lithographic plate using decalcomania paper, with machines then used to mass-produce the handbills. Printers also adopted chromolithography and other new technologies from the West.

This section explores these diverse handbill printing techniques

Chapter Three: The Artists Behind Hikifuda Designs

With the advent of mass machine printing, small stores across Japan could now afford to purchase hikifuda, with over 10 million handbills distributed each year during the late Meiji era. This prevalence encouraged more painters from a diverse range of backgrounds to engage with handbill design. Recent research has revealed the names of over such 100 artists. These include artists steeped in the ukiyo-e traditions of the Hasegawa and Utagawa schools, for example, as well as renowned Japanese and Western-style painters. The list also includes many obscure artists whose names only appear in the field of handbill design.

This chapter introduces the artists engaged in handbill production.

Chapter Four: Hikifuda Handbills and Beloved Stories

As well as celebrating the new year, most hikifuda handbills feature auspicious motifs symbolizing long life, prosperity, business success and social advancement, for instance. They often portray scenes from famous stories, such as Momotaro carrying treasure after vanquishing demons, a tongue-cut sparrow granting riches to an honest old man, and a seed-sewing peasant becoming the richest man in his village. These scenes portray people achieving wealth and success through courage, honesty and hard work.

This chapter features handbills decorated with these beloved scenes.

Chapter Five: Hikifuda Portrayals of a Dawning New Age

In addition to traditional auspicious symbols, hikifuda handbills also incorporated scenes of modernity. These included vivid depictions of new forms of transportation like steam trains, cars and airplanes, new forms of communication like mail and telephone, and people engaged in thoroughly modern pursuits like playing Western instruments, keeping dogs, and travelling by train. This was an age before television and the internet, when people lived in regions cut off from the latest news, so handbills were also a good way to find out about the latest urban trends. People were captivated and surprised by these colorful depictions of a new culture. The handbills also conveyed a sense of the prosperity and development sweeping Japan.

This chapter features handbills adorned with scenes of an alluring new age.

Chapter Six: Scenes of Business and Commerce

Hikifuda handbills portray a diverse range of industries, from farming to fishing, as well as a rich variety of different stores, from foods shops selling rice, dried foods and alcohol to clothes shops selling kimono fabrics and footwear. In this way, stores could inform customers about their business, with New Year handbills proving a great opportunity to depict scenes of roaring trade and happy shoppers. For instance, the handbill for a socks merchant would vividly portray the different stages of the socks business, from manufacturing to sales. Handbill purchasers would write their store name and New Year greeting in the white space before handing out the handbills to regular customers.

This chapter introduces handbills adorned with business scenes and store information written in the blank spaces.

Chapter Seven: Depictions of Gods of Wealth

Hikifuda handbills often feature deities associated with wealth, such as the Shichifukujin (Seven Gods of Good Fortune), Fukusuke, and Otafuku. The most popular of these were Ebisu and Daikoku. These two deities feature on a quarter of the handbills in our museum’s collection. They are shown riding in balloons, viewing cherry blossoms, or even hiding away on the top on someone’s hat. Gods of wealth are traditionally portrayed as charming and amiable. These characteristics were emphasized during the late Meiji period, with the gods portrayed more like friendly characters than deities.

This chapter features several depictions of these much-loved gods of wealth.